R261

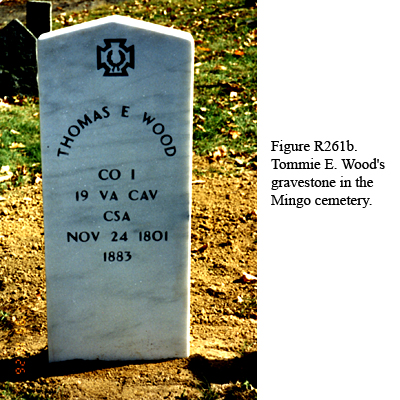

Husband: Thomas (Tommie) Epperson Wood (Fig. R261a)

Father: Carlos Wood [R250]

Mother: Glaffery (Bailey) Wood [R250]

Born: 11/24/1801 in Prince Edward County Va.

Died: 1883, at age 82, in Randolph County W.Va.; buried in Mingo

cemetery (Fig. R261b)

Wife: Sarah (Sally) (Moore) Wood (Fig. R261a)

Father: Thomas A. Moore [R260]

Mother: Martha (Wood) Moore [R260]

Born: 1812 [S059]

Died: 12/9/1883, age 73, of “fever” [S057]. Buried in Mingo Cemetery

Married: ~5/6/1834, in Botetourt County. Bond posted on that date

[S008]

Children:

Davis Morton Wood, b. ~1836

George Wood (not listed in 1850 or 1860 census; probably died young)

Joseph Wood, b. ~1841

Mac Davis Wood (not listed in 1850 or 1860 census; probably died

young)

Clarinda Wood, b. ~1844. Committed to the Weston State Hospital

(insane asylum), died there.

James B. Wood, 4/18/1848-10/9/1925, m. 5/4/1868 to Millard Ann Hall

(dau. of John T. and Susan Hall), s. Davis E. Wood (b. 1873, m. 1895

to Berdilia Tolley, dau. of J. F. and Melissa [Havener] Tolley)

Andrew Jackson Wood [R271], 10/15/1850-8/8/1943

Tommie’s movements in the first years of his life are unclear. By 1820 he appears already to have been living independently, because his father Carlos [R250] is shown living alone in that year’s census of Bath County. On 5/27/1825 Tommie, in company with his brother James Morton [R251] and his uncle Edward [R003], purchased land from Brown Jenks in Pocahontas County (now W.Va.). Tommie bought lot T1 in Fig. R003c, 2000 acres, for $750 (DB1-171). In 1827 he renegotiated the purchase with Jenks for an additional $150 (DB1-353); the property newly defined occupied T2 rather than T1 (however, the deed makes it sound like Tommie owned all of T1 plus T2). In the same year Tommie sold T2 (1435 acres) to Robert H. Beale for $1435 (DB1-358). The deed book speaks of Thomas and Sarah of Botetourt County selling the land, which is puzzling because Tommie and Sarah were not married until 1834.

In 1833 Tommie bought an undivided half of tract No. 8 (5000 acres) in Fig. R003c from Brown Jenks for $250 (DB2-185). This was in Pocahontas County; in the same year he bought lot T3, 200 acres in Randolph County, from Jenks for $90 (Randolph County DB11-170). In 1834, Tommie married Sarah Moore in Botetourt County Va. Apparently they lived at first in Botetourt County because their first child, Davis, was born there (according to 1850 Bath County census information). Sometime after 1836 Tommie and Sarah moved to their new land. It is not clear which of the tracts they homesteaded, but the Bath County deed book (below) refers to Tommie as being “of Pocahontas County,” which would rule out T3. They stayed there only briefly.

In 1840 Tommie and his half-brother James Morton moved to Bath County. On the same day, 5/5/1840, both bought neighboring parcels of property a few miles north of Millboro Springs, on Wilson’s Run (the name given then to Pig Run). The deed book describes the two as being “of Pocahontas County.” Tommie bought 180 acres of land from David and Mary Gibson for $900 (DB9-316).

DB10-86, DB10-99, and DB10-100 recount Tommie’s sale and repurchase of his property as a Deed in Trust in 1841 and 1842, to raise some money. Money seems to have been a problem: in 1841 Tommie defaulted on a debt of $39.34 to James T. Walron & Bros., merchants in Panther’s Gap, Rockbridge County, and was ordered by the court to pay with interest and court costs [S118]. Also in 1841 Tommie sold six notes he held to an Addison Dold for $100 plus a loan of $50, which he needed to prevent the sale of his property. The notes were loans to Joseph Moore [R350] and John W. Moore [R354], of aggregate value $324. In 1844 Tommie sued Dold for usury. The case was very complicated, but in 1846 the court awarded Tommie $100. Dold appealed, and I don’t know the final outcome [S118]. In 1842 Tommie sold his interest in tract No. 8, Pocahontas County, to William Sharp for $1500 (Pocahontas County DB3-514).

The 1850 Bath County census lists Tommie’s profession as “shoemaker.” His household consisted of wife Sarah; Davis, Joseph, Clarinda, James, and a Jane Davis (18, b. in Fluvanna County). He and Sarah were in Bath County as late as 1852, when they sold their share of the property Sarah inherited from her parents in Botetourt County [see R260]. Within the next eight years, he returned to Randolph County. The 1860 census of that county lists Tommie and Sarah with children Davis, Martha C. (Clarinda), James, and Andrew. The census enumeration shows their property was adjacent to that of Joseph Moore and the other Edward Wood children and in-laws. This may have been tract T3. However, according to family tradition in Mingo, at the time of the Civil War Tommie didn’t own property in Randolph County, he just “lived here and there,” specifically up Logan Run near the Ware cemetery.

When the Civil War came Tommie was old enough to sit it out, but instead he fought for the Confederacy and achieved mythic stature. I quote from [S108]:

“When Gen. Lee was camping on Valley Mountain, close to Mace, West Virginia, during the first year of the War, Thomas joined his troops and was appointed a scout by Gen. Lee. Possibly the first exploit as a scout occurred in what is now F. P. Marshall’s meadow. He was returning to Lee’s camp on a scouting expedition and as he came up off the Tygart Valley River, in sight of the meadow, he saw two soldiers some distance from him. At the same time the two soldiers also saw him. One of the two men, Jacob Gibson, said to his companion Billie Wilson, ‘I see a man coming through the meadow over there. I shall just wait until he comes over here and if he isn’t the right stripe I shall take a shot at him.’ Gibson was a Yankee and of course Tommie was of the wrong stripe. So when Tommie came within speaking distance of Gibson he (Tommie) ordered Gibson to surrender, but Gibson wasn’t disposed to surrender so he fired his pistol at Tommie but missed. Tommie then fired at Gibson, the bullet striking Gibson in the mouth and knocking out his front teeth. This blow knocked Gibson off his horse, and by darting into some under brush, he was able to escape, leaving Tommie ln possession of his horse, gun, etc. Later during the war Gibson was killed at the breastworks at Old Fort (Elkwater). Tommie was present, on the side of the victors, and as Gibson was being buried, Tommie pried open the mouth of the corpse. Someone asked him his purpose for doing it and he replied, ‘I just wanted to see how near I came to killing Gibson some time ago.’

“During the year of 1861, the Union forces under McClellan had fortified themselves on White Top on Cheat Mountain. Because of the importance of the Staunton-Parkersburg turnpike, as a means of convoying supplies from East to West the Confederates wished to obtain possession of’ the location held by the Union Army. Consequently Gen. Rust, the Confederate general located at Huntersville, West Virginia, sent Tommie Wood as a scout to make a reconnoiter of the situation, and if possible to determine a good route by which the Confederate forces might make a surprise attack upon the Union Army.

“Tommie made his way to the encampment of the Union Army and made a favorable survey of the location and started back to Rust’s Army at Huntersville by the route which later became known as Rust’s Trail. As he returned, somewhere about two miles this side of White Top he came upon a Union soldier riding a mule. Tommie ordered the soldier to surrender, but the soldier replied in a very light manner that, ‘My mule is a very swift one.’ This seemed to arouse Tommie’s fighting spirit so he replied, ‘Yes, but he isn’t as fast as my old rifle.’ So he shot the man and wounded him very badly. Tommie searched him and found that he was a Union scout and at the time in possession of some very valuable information. Tommie took all the soldiers reports, gun, and mule. Before he left the soldier asked for a drink of water but Tommie replied, ‘There’s no water nigh.’ So he sat the wounded man up against a tree and passed on. It seems that the soldier died in that position and his bones were seen at that place more than a year later.

“Tommie returned and reported to Rust that he found a favorable route which Rust led his army [on] but because of some mistakes in his instructions he never made the attack. Afterwards people would ask Tommie where he ran across his white mule [and] he would reply, ‘I killed a Yankee and got him.’

“In 1861 Capt. J. W. Marshall received the information that a party of Union soldiers were staying at Polly Gibson’s on the headwaters of the Elk River. So he collected seven or eight Confederate soldiers to go with him and capture them. Tommie was one of the volunteers. They approached the house and were seen by the Union soldiers who began to shoot at them, but the Confederate soldiers made it too hot for them Yankees, so they started to run. Jake Simmons was one of the Yankees and as he started to run he recognized Tommie and because of his animosity toward Tommie, stopped by a rail fence and took a shot at Tommie. He missed his mark and before he could make himself scarce Tommie fired and came so close to his head that it knocked a lot of splinters off the rail fence which penetrated the flesh of Simmon’s face. Simmons never stopped to pull the splinters out but kept running until he reached A. C. Logan’s near Valley Head, West Virginia, where he had the splinters removed and told how he happened by them.

“Tommie came to Mingo on a few days absence and on his return to Huntersville, he was caught in a terrible rain and snow storm. He went ahead until he was nearly frozen then he decided to try to spend the night with a Union man by the name of Johnson, who lived close by the Greenbrier River. Tommie approached the house and knocked on the door which was opened by Johnson himself. Johnson was well acquainted with Joe Wood, a brother of Tommie’s who was a Yankee. As it was dark and it had been a long time since he had seen Joe, Johnson mistook Tommie for his brother, Joe, and said, ‘This is Brother Joe Wood, isn’t it?’ and Tommie replied, ‘Yes sir, this is Joe Wood.’ Tommie was well aware of his danger, but was acquainted with the knowledge of the friendship and acquaintances which existed between his brother Joe and Johnson, so he decided to pass himself as his brother. Joe Wood and Johnson had often held prayer services together, so during the conversations which followed, Johnson spoke of their good times in the past, to which Tommie had to respond very readily. Tommie afterwards said, ‘I broke the ice by offering Grace at the supper table.’ Before they retired for the night, Johnson placed the Bible and a candle on the table and Tommie knew what was expected of him so he read from the Bible and then offered Prayer. During the course of Prayer he, of course, much against his will, prayed very earnestly for the Union Army and their success. Afterwards someone said, ‘Uncle Tommie, why did you pray for the Union?’ Tommie replied with a smile, ‘It didn’t do any harm to pray for them once in a while, especially under such circumstances.’ The next morning Tommie asked Johnson to row him across the Greenbrier River. During the trip across the river, Johnson began to be enlightened of his mistaken identity and said, ‘I had a notion to hit Tommie over the head with my canoe pole, but wasn’t quite sure of my mistake.’ But Tommie said, ‘I was watching that canoe pole.’

“During the second year of the war, 1862, Capt. J. W. Marshall again gathered up a handful of men and started to the Little Levels in Pocahontas County to capture some Yankees who were camped in an old vacant house in that section. The Yankees were prepared for the attack by having taken the mud out from between the logs in the house, which were fine portholes. So when the Rebels approached the Yankees began to open fire on them. The Rebels began to look for cover and concealed themselves behind some out buildings. During the fight which followed three of the Rebels were wounded and all but one of the Yankees were killed. Tommie Wood was among the Rebels who were wounded. He was standing behind a corncrib and as he raised up to shoot a Yankee shot him through the intestines, the ball coming out beside the backbone. The other soldiers thought he had received his death wound. Capt. Marshall asked if he had any word to leave to his family, but Tommie replied, ‘I’m not going to die yet.’ He was taken to Colonel McNeal’s where he remained the rest of the winter. His wife Sally was informed of the wounding, and rode a white horse through the battle area to where Tommie was and stayed with him until he recovered enough to come home. [Another version says in the spring Tommie was taken to Sam Wood’s on the Cow Pasture River in Virginia where he finally recovered from his wound. I don’t know who this Sam Wood would be.] This practically ended his activities in the war.”

In fact the military records show that Tommie formally enlisted as a Private in Capt. Marshall’s Company (Company I, 19th Virginia Cavalry) after these exploits, on 2/1/1863, at Huntersville W.Va. (then the county seat of Pocahontas County). This regiment was composed principally of former members of the 3rd Regiment, Virginia State Line. Records of subsequent Company muster roll-calls through 10/31/1864 all show him absent, wounded. He signed a parole on 4/9/1865.

The 1870 census of Randolph County shows Tommie (65, Farmer) and Sally (59, Keep house) living with their son James (22, Farmer), his wife Mildred Ann (25, Keep house), and son Andrew (18).

One other Tommie Wood legend [S119]: “The how and why of Tommy Woods and his miraculous cure of mountain children back in the days before the Civil War is a suitable subject for medical research. The folks up in Green Woods said because Tommy had had his hand in the mouth of a dying wolf he could cure the little folks of many diseases in the winter when food was scarce. It seems that he had only to put his finger in the little sufferer’s mouth, speak a friendly word, and there was improvement. But the young, new Doctor up Green Woods way says that the light of science only needs to be thrown upon the old superstitions in order to dissipate them like the mists of the morning. And until his coming no importance was attached to the bit of raw vegetable given each child with the touch of the healing finger. He says that the living vitamins of the raw potato and not the dying wolf should be credited with the cures.” (I can’t locate a “Green Woods” on maps of the vicinity of Mingo W.Va. Could this be a reference to Green Valley, close to Tommie’s farm on Pig Run in Bath County?)

Sources: [S030, S031, S032, S057, S059, S077, S096, S097, S104, S105, S106, S107, S108]