R004

Husband: Francis Marion (Frank) Wood

Father: Edward Wood [R003]

Mother: Sarah (Gilliland) Wood [R003]

Born: 3/25/1830 [S031]

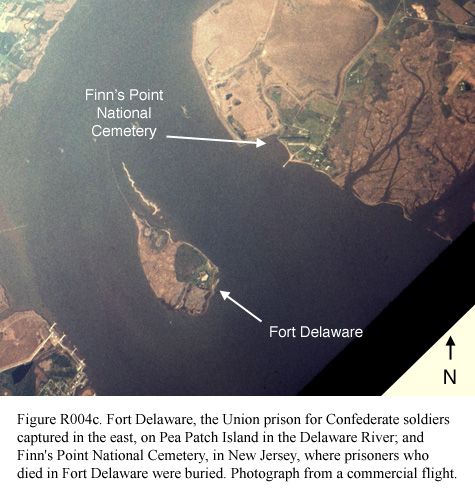

Died: 10/2/1863, a Confederate prisoner at Fort Delaware, Del. [S019].

Buried at Finns Point National Cemetery, N.J.

Wife: Rebecca Young (Entsminger) Wood

Father: Lewis C. Entsminger [R400]

Mother: Margaret (Ford) Entsminger [R400]

Born: 3/27/1839

Died: 9/25/1901, at the home of her daughter Martha Ann (Wood) Burger [R450] in Covington Va.; buried in the Goshen, Va. Baptist Church cemetery.

Married: 11/7/1854, in Rockbridge County, Va.

(2011) Francis Marion Wood was born in the White House in 1830. He undoubtedly was named for Gen. Francis Marion of South Carolina (1732?-1795), the widely admired “Swamp Fox” of the Revolutionary War [S037]. Several documents, such as the 1860 census, confirm what you would expect, that he went by the name of “Frank.”

About 1849, Frank’s father died intestate. In 1854, acting in accordance with Edward’s expressed wishes, his heirs sold the five tracts of land spoken of in [R003] which had comprised Edward’s Bath County homestead, including the White House, to Frank for $1 [R904].

Prior to this agreement the 1850 census of Bath County found Frank living in the household of his sister Elvira and her husband John Armentrout [R352], whose property abutted Edward Wood’s on the east, perhaps because Frank’s mother and some of his brothers and sisters still occupied the White House. The census lists the following members of the Armentrout household, all born in Bath County:

John Armentrout, farmer, age 29

Elvira Armentrout, age 24

Francis Wood, age 20

John Wood, age 22

Thomas Pleasant, blacksmith, age 20

Joseph Pleasant, apprentice, age 17

John Wood was Frank’s brother John Carter Wood [R362]. (Actually, according to [S031] both John and Elvira turned 26 in 1850, having been born ten months apart in 1824.)

Frank was married in November of 1854 in Rockbridge County, six months before the above property settlement occurred: “Married, on the 7th inst., by Rev. Samuel Kepler, Mr. Francis M. Wood to Miss Rebecca Y., daughter of Lewis C. Entsminger, Esq., of Rockbridge county, Virginia.” —Bath County Gazette, 11/16/1854. (However, their marriage certificate gives the date as 11/8 [S071]).

Rebecca was raised in Collierstown Va., a town about eight miles (as the crow flies) west of Lexington and eleven miles southeast of Frank’s home. She was 15 years old at marriage, Frank 24. Frank’s mother had died by then, and he and Rebecca made their home in the White house [R020] [S021].

Children of the union were:

Martha Ann (Mattie) (Wood) Burger, b. 9/8/1855 [R450]

Lewis Edward Wood, 12/18/1856-5/8/1948 [R005]

James O. Wood, 10/26/1858-9/29/1941 [R451]

Americus (or America) J. Wood, b. 8/13/1859 or 1860 (died young of diphtheria; buried in Indian Hill cemetery) [S053]

John M. Wood, 9/1861-11/10/1861

Lucy (Wood) Dill, b. 11/1862 [R452]

Frank and Rebecca proudly named Lewis Edward, their first son, after both of his grandfathers. Rebecca returned to her parent’s home in Collierstown for the accouchement, and brought Lewis Edward back when he was three weeks old [S003].

Frank had only a few years to enjoy his inheritance, his wife, and his children: he fought and died in the Civil War. At the Bath County Courthouse on 6/6/1861, shortly after Virginia seceded from the union (4/17), he enlisted for one year in the Bath Grays, a local volunteer infantry militia unit [S013]. The Bath Grays, which were Company G of the 25th Regiment of Virginia Volunteers, participated in an unsuccessful defensive battle at Rich Mountain, W.Va. on 7/11/1861 [R024], one of the first important actions of the war. On this occasion the entire company was captured, including Frank [S062, S071].

The captured Bath Grays were paroled and exchanged on July 17. No picture of Frank survives, to my knowledge, but his parole document describes him: 5’ 10” in height, light complexion, light hair, blue eyes. After exchange the remnant of the company is reported to have been assigned to Company A, 62nd Regiment of Virginia Infantry. The first of two surviving letters from Frank to Rebecca (Fig. R004a) was written on 10/31/62 while Frank was serving as a Private in that company; the Regiment was stationed in Highland County, Va. It is late in the harvest season, and Frank is preoccupied with getting home to do the work that needs to be done. He asks Rebecca to find a substitute for him, either a temporary one or for the rest of the war, so he can do this, and in case she can’t, he gives her detailed instructions on running the farm herself. He asks about a visit from “gustus,” who would be his oldest brother Augustus [R361] from Randolph County.

The 2/28/1863 role of Company A, 62nd Regt. states that Frank deserted “about 12/1/1862” and enlisted in a cavalry company. Most of the rest of his old company did the same. The 3/31/1863 role for Company E (later G) of the 18th Regiment of Virginia Cavalry notes that Frank enlisted in that unit on 12/3/1862, at Camp Washington (presumably the name given to an encampment in Bath County), for the war. His rank in this Regiment was Third Sergeant. Members of the 18th Cavalry Regiment were recruited mostly from the counties of western Virginia: Hampshire, Hardy, Pendleton, Tucker, Barbour, Upshur, Lewis, Randolph, Pocahontas, Webster, and Braxton Counties in what is now West Virginia; and Frederick, Shenandoah, Rockingham, Augusta, Highland, and Bath Counties in Virginia. It was organized by Col. (later Gen.) John D. Imboden of Staunton, about the time Frank enlisted, and it operated mostly as a semi-autonomous force in the mountain counties.

Frank’s second letter (Fig. R004b) was written on 4/13/1863 while he was serving with the 18th Cavalry and stationed in Williamsville, on the Bath/Highland County boundary. He is mostly concerned with buying scarce commodities that Rebecca needs and conveying them to her via “Mr Steward” in Millborough. At one point he recommends that Rebecca “send wess [?] to Millborough”: was this a nickname for their eldest son Lewis [R005]? He was only six when the letter was written, pretty young for such a long and crucial mission. Frank also speculates that his Regiment is about to move on Beverly, the county seat of Randolph County, the county where many of his brothers and sisters lived. The latter were Confederate in their sympathies, but the county was occupied by the Union Army.

Frank was right: a week after he wrote his letter (now Gen.) Imboden’s command, consisting of the 18th Virginia Cavalry, six other regiments, and McClanahan’s Artillery Battery, departed McDowell (Highland County) in the direction of Beverly. The aggregate force under Gen. Imboden was ~3365 men, of whom 700 were mounted. The 18th Virginia Cavalry was commanded by Col. George W. Imboden, Gen. John Imboden’s brother (the name Imboden is of Swiss origin). They arrived in Beverly on the 24th and defeated the Federal garrison in a brief battle. The 18th Cavalry pursued the retreating enemy for six miles, but most were able to make their escape. The regiment then entered Beverly, where one of its number said they were “kindly received by the ladies” [S013].

After the regiment had engaged in several other minor actions in the mountain counties in the spring of 1863, on June 7th Gen. Imboden received orders to carry out a series of covering actions on the left flank of Lee’s main army as he moved north into Pennsylvania. During this campaign Gen. Imboden’s command consisted of the 18th Virginia Cavalry, the 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry, the Virginia Partisan Rangers, and McClanahan’s Battery; about 2000 effective horsemen plus artillery. The unit was referred to simply as “Imboden’s Command,” and operated apart from the rest of the Confederate cavalry, which was commanded by Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart [S022].

Gens. Lee and Stuart, and other Confederates, did not have a high opinion of Imboden’s Command. As [S023] puts it, “In addition to the regular cavalry Lee ordered another mounted force under Brigadier General John D. Imboden to be ready to accompany the Confederate drive to the north. Imboden had under him an assortment of armed riders even more unruly and untrained than Jenkins’ and possessing a well-developed proclivity to rob civilians, especially of their horses. Operating as a rule in the Shenandoah Valley, in the spring with some help from “Grumble” Jones [Gen. William E. Jones, an infantry commander], Imboden had raided Yankee-held territory in western Virginia [the Beverly campaign]. Militarily the affair had not amounted to much, but it did result in the seizure of supplies highly cherished in the Southern economy of scarcity. In pitched battles with veteran enemy cavalry Imboden’s force was of questionable value, but his men could ride and shoot. Their skills were highly useful for widespread foraging in poorly defended regions of the North and for guarding supply bases and wagon trains. In its semi-independent status the command served in an auxiliary capacity during the Gettysburg campaign.”

On June 29th, Company G of the 18th Virginia Cavalry (Frank’s Company) was sent to scout in McConnellsburg PA, which is ~44 miles west of Gettysburg. There the 1st New York Cavalry caught them by surprise, killing two and capturing 30 of them (one and 22 according to another account), including Captain Ervin, the Company commander. Given that Confederate military units were chronically understrength (Company G probably consisted of less than 100 soldiers), this means a sizeable fraction of the Company was captured. According to [S013], “the circumstances leading to the incident are unclear, but it is evident that Company G was not properly vigilant. In a July 1st correspondence to General Imboden concerning the incident, General Lee wrote, ‘I regret the capture of Capt Irwin (sic) and part of his company at McConnellsburg, especially as it appears to have been the result of want of proper caution on his part. I hope it will have the effect of teaching proper circumspection in future.’”

The battle of Gettysburg lasted through the first three days of July; on July 4 Lee began his retreat. Frank was captured during the battle. According to records at the Fort Delaware federal prison where he was sent [S019], and the National Archives [S088], he was captured on July 3 1863. This was the climactic day of the Gettysburg battle. However, Imboden’s Command was not engaged in combat on the 3rd; or on the 1st or 2nd either, for that matter. [S013] says the unit performed rearguard duty on the 1st and 2nd, and on the 3rd the 18th Va. Cavalry “was moved up the Chambersburg Pike to a point just west of [i.e., behind] the main Confederate line on Seminary Ridge, and that they remained in this position throughout the fighting of the 3rd day. After dark they fell back five miles and went on picket duty. Later that night General Imboden received verbal orders from General Lee to guard the wagon train on its return to Virginia.”

It is a mystery how Frank got in trouble on the 3rd. In its systematic commentary on all the members of the regiment for whom information is available, [S013] notes for about 20 members of Co. G that they were captured at McConnellsburg; but Frank is the only member of the company reported to be captured at Gettysburg. He was sent as a prisoner, along with most of the other Confederates captured at Gettysburg, to Fort Delaware, on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River (about seven miles south of the present Delaware Memorial Bridge). It took four or five days from the time of capture for prisoners to reach Fort Delaware [S019].

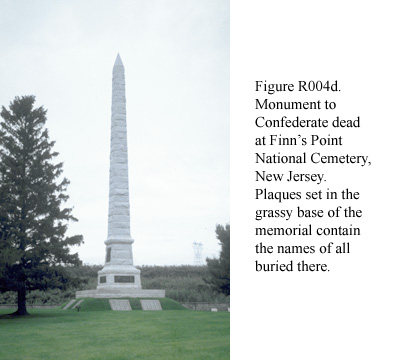

On October 2 1863 Frank, 33, died of “chronic dysentery.” Fourteen other prisoners, ten from Gettysburg, also died at Fort Delaware that day, all from disease rather than wounds. All were buried on the “Jersey Shore” [S019] in what is now the Finn’s Point National Cemetery (see [S036]). The Cemetery now consists of a large grassy field under which the prisoners are buried in unmarked graves; in one corner stands a massive gray granite monument (Fig. R004d), heavy in the nineteenth-century Civil War memorial style, inscribed

ERECTED BY THE UNITED STATES

TO MARK THE BURIAL PLACE

OF

2436 CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS

WHO DIED AT FORT DELAWARE

WHILE PRISONERS OF WAR

AND WHOSE GRAVES CANNOT

NOW BE INDIVIDUALLY IDENTIFIED

Around the base of the monument the names of those buried there, including Frank’s, are cast in bronze tablets (Fig. R004e).

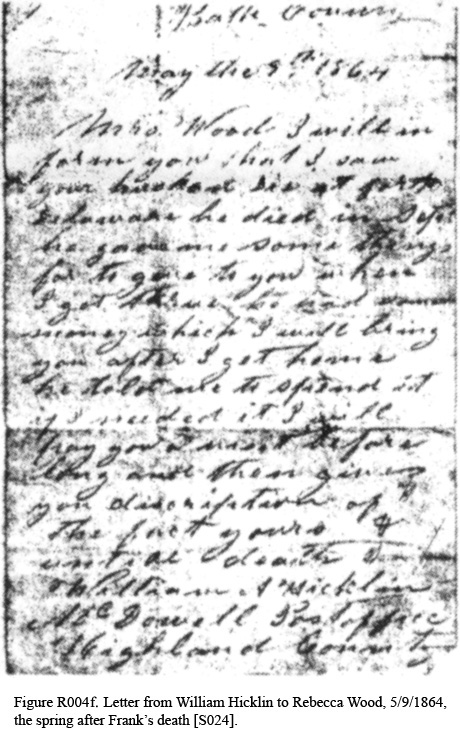

The spring after Frank’s death, Rebecca received the letter shown in Fig. R004f. William Hicklin had been a private in Frank’s company; he was captured at McConnellsburg and sent to Fort Delaware. On 10/26/1864, after Frank died, Hicklin was transferred to Point Lookout, Md., then on 4/27/1864 he was exchanged. He was admitted to Chimborazo Hospital No. 3 in Richmond on 5/1 for “Hayes operation left foot.” On 5/8, the day before he wrote to Rebecca, he was granted a 30-day furlough [S013].

Rebecca was 25 years old when she was widowed. She had the hard job of seeing the farm and four small children through the Civil War years. Every time Union raiding parties were rumored to be approaching, she had to assemble her children and livestock, pack or hide her valuables, and flee to the mountains [S021]. Before Frank’s death, a worse problem than Yankee raiding parties had overtaken Rebecca; she became pregnant at a time that did not square with her husband’s last furlough from the army. When labor began, she retired alone to an upstairs room in the White house. Afterward, she did not produce a baby or an explanation. Her neighbors assumed the worst, and thereafter she was widely ostracized.

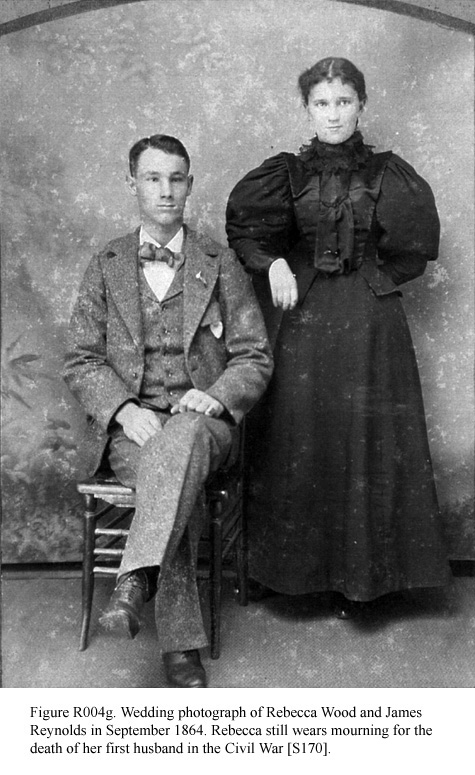

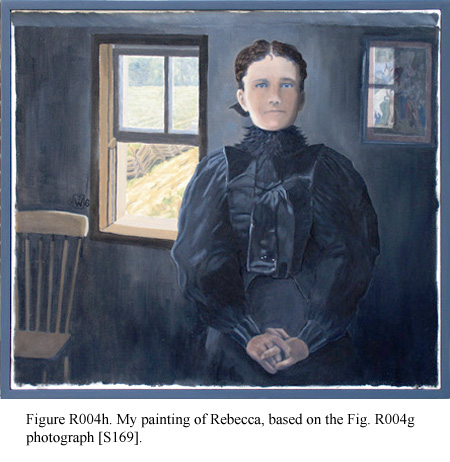

About a year after Frank’s death Rebecca married her cousin James Reynolds, 24 (Fig. R004g). Their families had both belonged to the Collierstown Presbyterian Church.

Rebecca’s second husband: James Forsythe Reynolds

Father: George Reynolds [R401]

Mother: Elisabeth (Forsythe) Reynolds [R401]

Born: 1840, in Rockbridge County

Died: 1/9/1901 [S170]

Married: 9/29/1864, at Warm Springs, Bath County. Minister: Thomas Bailey.

Children: (all born in Bath County)

Mary E. J. (Reynolds) Lawrence, b. 1866 [R453]

Francis M. Reynolds, b. 1868 [R454]

Virginia Etta Reynolds, 1871-2/21/1892 (aged 21)

Margaret (Maggie) (Reynolds) Trueblood, b. 1872 [R455]

Samuel Jordan Reynolds, 3/1874-2/1/1892 (aged 18)

Fremont Houston Reynolds, b. 1876 [R456]

Gratton Reynolds, 12/25/1879-5/6/1939 [R459]

Alice (Reynolds) Wilkerson [R457], b. 1881, d. 1947 in Gaithersburg,

Md.

Frank Wood’s children lived with James and Rebecca at the White House until they grew up. The 1870 census shows Frank Wood’s four children, seven years and more old, and three of James Reynolds’s children, three years and less old, in the same household. Frank Wood had died intestate. His personal property was inventoried in 1866; its net value was $622.34 [R905]. I have not learned how it was liquidated or how the proceeds were distributed. Each of Frank’s surviving children received one undivided fourth of his land holdings (i.e., one-fourth interest in the whole estate; not a specifically carved-out fourth of the land). However, either this was not effective until they turned 21 (or in the case of the girls until they married), or they could not sell their interest until that time, because once they did achieve their majorities they promptly sold their bequests: Mattie (married) in 1876, at age 21 (DB13-114); and Lewis Edward (24), James (22), and Lucy (18, married) in 1880 (DB16-84).

This is probably and logically the time when James and Rebecca Reynolds left the White House. Apparently they moved to a farm on Mill Creek in Bath County. The stream follows Rte. 39 much of the way from Millboro Springs to Goshen (in Rockbridge County). Later (2/2/1889) they sold 193 acres of land there, presumably the property they had been living on, to Rebecca’s son Jim Wood [R451] (DB16-513, 514). Living there would explain Rebecca’s affiliation with the Goshen Baptist Church: when children Virginia Etta and Samuel Jordan Reynolds died in 1892, they were buried in the cemetery of that church. It is unclear where James and Rebecca went to live after Mill Creek. Rebecca died 9/25/1901, and was buried next to Virginia Etta and Samuel Jordan. The Wood family Bible [S003] says she “Died in Covington, Virginia, July, 1901 at the age of 63.” It seems likely she lived her last years with her daughter, Maggie Trueblood [R455], in Covington. A third child, Alice Wilkerson, was buried in the Goshen churchyard much later (1947). There is no stone for Rebecca’s husband, James Reynolds. [S071] understands that he succumbed to cancer before Rebecca died, and was cremated.

Family tradition is that James Reynolds was a very gentle person, but Rebecca was quite strict [S071]. Interestingly, it was in this generation that the Wood line made the switch from the Presbyterian to the Baptist church; one would like to know how it happened. Edward Wood had been a stalwart Presbyterian, and both the Entsminger and the Reynolds families were pillars of the Collierstown Presbyterian Church; but Rebecca’s son Lewis Edward Wood [R005] was a stern Baptist, and by [S071]’s account the Reynolds children Margaret Trueblood and Frank M. Reynolds were too. Mary Lawrence, on the other hand, stayed Presbyterian.

Francis M. Reynolds [R454] obviously was named in honor of Rebecca’s first husband. Frank Wood’s name was also passed down to Lewis E. Wood’s last son [R563], and from him to his daughter and granddaughter.

Sources: [S007, S013, S017, S019, S021, S052, S053, S054, S062, S071, S088, S117]