R021

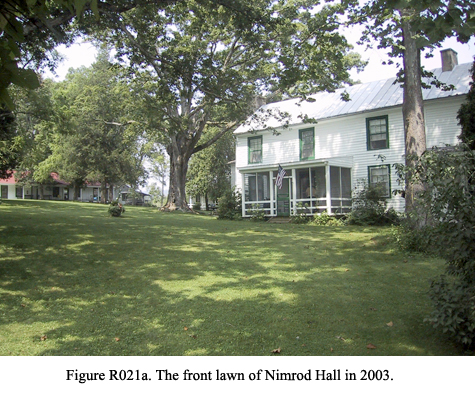

Nimrod Hall (Figs. R021a, R021b; 2011)

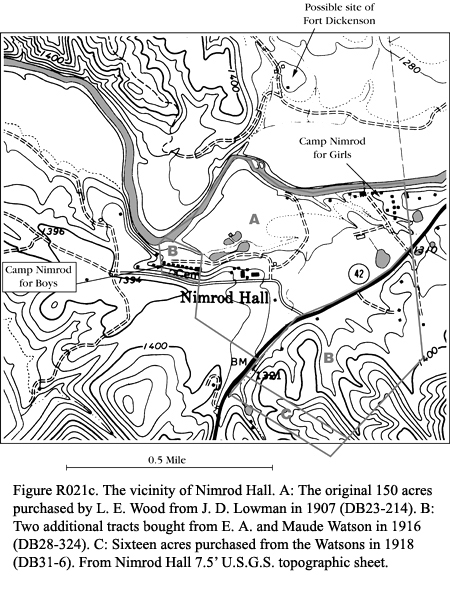

Nimrod Hall is a fine old country estate sited on the gently-sloping crest of a NE-SW trending ridge, about four miles SW of Millboro Springs. The land drops away ~1/4 mile NW to the Cowpasture River, and a similar distance SE to Rte. 42 (Fig. R021c). The view in either direction from Nimrod’s commanding position is spectacular. Lewis and Emma Wood [R005] spent the last part of their lives there. The place always exerted a magnetic attraction for their children, and still does for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who love to return and bask in its ambience. The diaries of their son Kemp Wood [R550] [S074] contain a number of affectionate entries about Nimrod; here are three of them, from 1951.

“AUGUST 19 NIMROD HALL

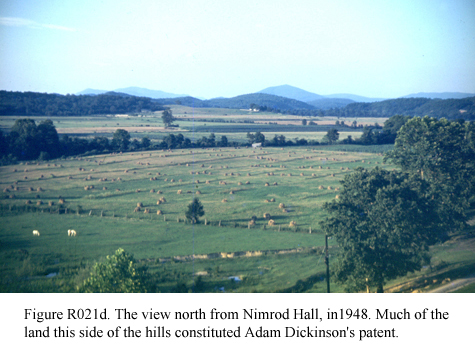

Just to be at the old place again. To walk around the grounds, to look across the fields, see the horses and cattle grazing, an old cow chewing her cood while leisurely standing under an old sycamore tree, a crow squawking yonder, to smell the new mown hay, and to eat fresh vegetables. One can admire the grandeur of the mountains, watch the moon creep over the mountain at night, watch the sun set at eventide, hear the crickets, grasshoppers and bugs chirp, the katydids call.

“AUGUST 21 FISHING ON THE OLD COWPASTURE

Just to go out with lunch in a paper bag, dip net for minnows, a paddle, rods and tackle, bait bucket, fish string, old clothes on, old shoes, ready for wading. Reaching some familiar haunt, one goes after helgrammites, mad toms, minnows, etc. All set and in the boat and after a pike, bass, yellow belly, red eye, or what not. Its fun excitement, even if no fish are caught. Just to be on the old river, to get wet up to the neck, hungry as a bear, and get home at night, tired, and a string of fish.

“AUGUST 30 FROM EAST PORCH-NIMROD HALL

One gets a good view of the Cowpasture River Valley with its spreading fields and surrounding hills and mountains. Across the river, to the left, is the Porter farm, above it, the Hawkins farm, and on above, the Withrow property. To the right, the filling station and store, operated by Russ– then, Oz Lucket’s place, and behind him, June Long. Burger’s house is just above the Motley home on the hill, and then Tucker Loan. Across the road is the Girl’s Camp, hidden in a cluster of trees, and above it Matt’s home on the hill. Highway 42 winds around the hills, plunges down and then up, bends around Island Hill and around the Withrow curve. One can see, on the left Rough Mountain with its shaggy ridges and uneven tops. In the distance, Mill Mountain, then towering Chestnut Ridge. On the other side of the river, the blue lines of the Warm Spring Mountain, then, Mares Mountain. Nearer is North Mountain. In between, and split the valley in twain, is the winding, snake like Cowpasture River. On and on it goes to finally empty in the James at Iron Gate, Thus, one gaze, admire, and drink in the beauty of it all.”

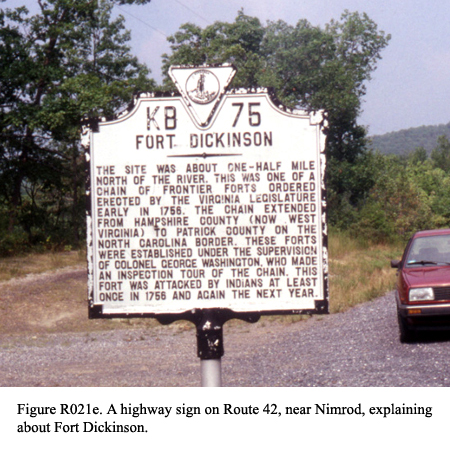

The site of Nimrod Hall was in a 1080-acre tract of land patented by the Crown to Adam Dickinson in 1750 (Fig. R021d). The sites of Fort Dickinson and the original Windy Cove Church were also in the tract. Adam Dickinson, a blacksmith, had been in Hanover N.J. in 1733. He migrated south to Augusta County Va. by 1744, via Lancaster Pa. and Prince George County Md. Adam willed his property to his only son, Col. John Dickinson (1731-1799), who pioneered settlement of the area between Millboro Springs and Nimrod and for whom Fort Dickinson (Figs. R021c, R021e) was named. John Dickinson's will, in turn, divided the property between his sons John N. Dickinson (who got the half Nimrod is in) and a junior Adam Dickinson (WB1-143).

Construction of the Nimrod Hall building was begun in 1783: this year is carved in the building’s handsome stone chimney, though of course the carving may have been done some time after that date. This was about the time when Indian raids ceased to be a serious threat in Bath County, though forts continued to be garrisoned in the County as late as 1789 [S040]. The original core of the Nimrod structure was built of logs; apparently it was two stories high from the beginning [S039].

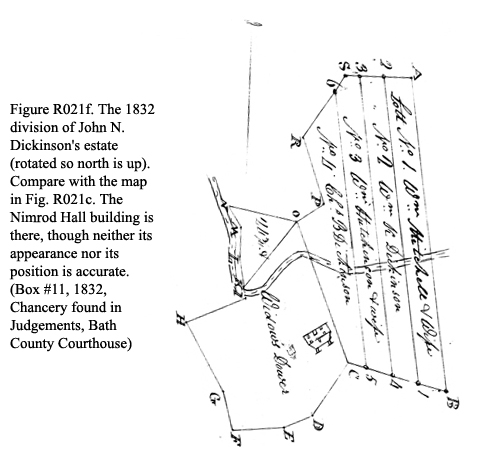

Upon John N. Dickinson's death intestate, his property was divided by the court (1832), with 1/3 (including the Nimrod property) going to his widow Charlotte Dickinson, the remainder being split between children John M., William K., Charles B., Caroline D., and Harriet Dickinson (Fig. R021f). In 1845 widow Charlotte, John, William, and Charles sold their shares of the property, 220 acres, to Andrew Sitlington and John P. Porter (Harriet had earlier sold her share to her mother) (DB10-398).

Ref. [S039] notes that an old lady visited Nimrod early in the 1900s, asked to be shown around, and pointed out the room where she was born at some time before 1845. She said the construction of Nimrod was begun by William Dickinson, of whom she was a descendent. It is unclear how this William Dickinson fits into the family tree; John N. Dickinson’s son William K. Dickenson was born too late to square with the 1783 chimney stone. [S039] further reports, “Andrew S. Porter who lived in this house, served in the War Between the States, in Company F, Eleventh Cavalry. In possession of E. S. Porter, son of Andrew S. Porter, the following was found, dated March 14, 1886. ‘I was wounded in the battle of the Wilderness, on the 4th day of May, 1864. I have this day found the ball after suffering twenty one years, ten months and ten days. I entered the Confederate service on the 12th. day of May, 1861. At the battle of Rich Mountain I was captured on the retreat from same. My age at that time was 16 years, 9 months. After I was exchanged, I joined Company F, of the Bath Cavalry at Winchester in October of 1861, and remained in said Company until I was wounded in 1864, and was in all the battles of the east during that time. --Andrew S. Porter’”

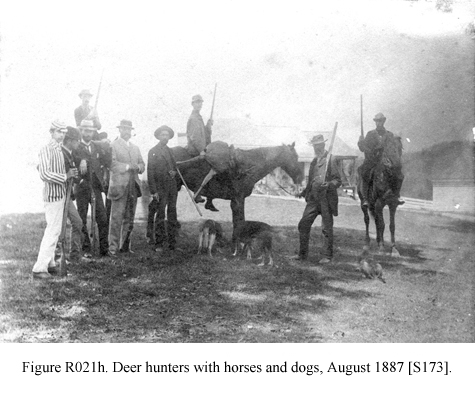

In 1873 John Porter sold Nimrod Hall to William W. Mooney, who in 1874 sold it to Dr. Henry E. Smith, from Amherst County. Smith and his family owned the property into the twentieth century. He was a lover of dogs and an enthusiastic hunter. His friends came to hunt with him; he and his wife Susan began accommodating guests on a commercial basis (Fig.R021g), and the number of guest rooms was expanded by new construction. Nineteenth-century photographs hanging in the dining hall show Victorian hunters of both sexes with guns, dogs, horses (it was legal to hunt deer in the summer, with dogs and horses, in those days), and the carcasses of deer in rigor mortis (Fig. R021h). A description of Nimrod in 1882 [R917], written by Gordon Blair decades after he visited as a 14-year old, is interesting to read. According to his account, by that time the county's deer had been hunted practically to extinction; and the name "Nimrod Hall" was given to the resort by the Smiths' daughter, Miss Annie ("Though received with amusement by the guests, the name stuck").

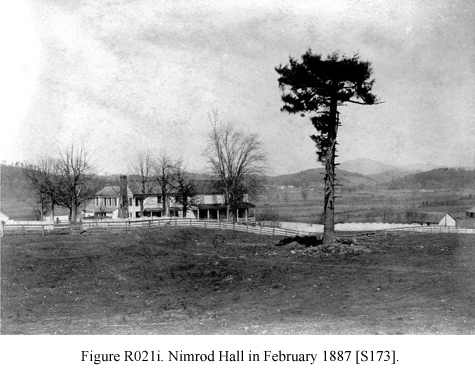

The original log structure of Nimrod became sheathed in clapboards in the nineteenth century, to hide the barbaric logs and make the style of the core building consistent with that of new two-story wings of frame construction that were added to the buildings in two directions (Fig. R021i). These have a network of porches, staircases, and passageways, all executed in a uniform country-Victorian style that gives the building the air of a beached Mark Twain river boat. Three additional buildings containing living quarters were built across the lawn from the main building. Most of this construction was done between 1887 and 1893: the 1887 picture (Fig. R021i), in the Smiths' time, shows the core building with only one of its wings (the NE one) and no supplementary buildings; photographs from about 1895 [S173], in E. A. Watson's time, show all the buildings that constitute Nimrod Hall today. Now the lawn is shaded by mature trees, but these early photographs show a situation that is much younger and more open to the sky and landscape.